Frequency Analysis on Repeating-key XOR

Repeating-key XOR is a simple, yet good exercise to learn how structure betrays secrecy. I’ll walk through the basic idea behind the encryption and how it can be broken: the intuition, the practical steps I thought of. I’ll also add a mention to a simple cipher I built months back, the Bit Flip Cipher and why the same weakness applies.

What is Repeating-key XOR

It is a simple encryption method where each byte of the plaintext is XORed with a key, and when the key runs out, it loops from the beginning. For example, if the key is three bytes long and the message is nine bytes long, the key is repeated three times such that every plaintext byte has a corresponding key byte. This makes the cipher easy to apply.

Since the key cycles in a fixed pattern, the same positions in the message are always affected by the same key bytes and it is this repetition that makes the scheme vulnerable to statistical attacks. One way of analysing the statistical properties of the ciphertext is to apply frequency analysis.

Frequency Analysis

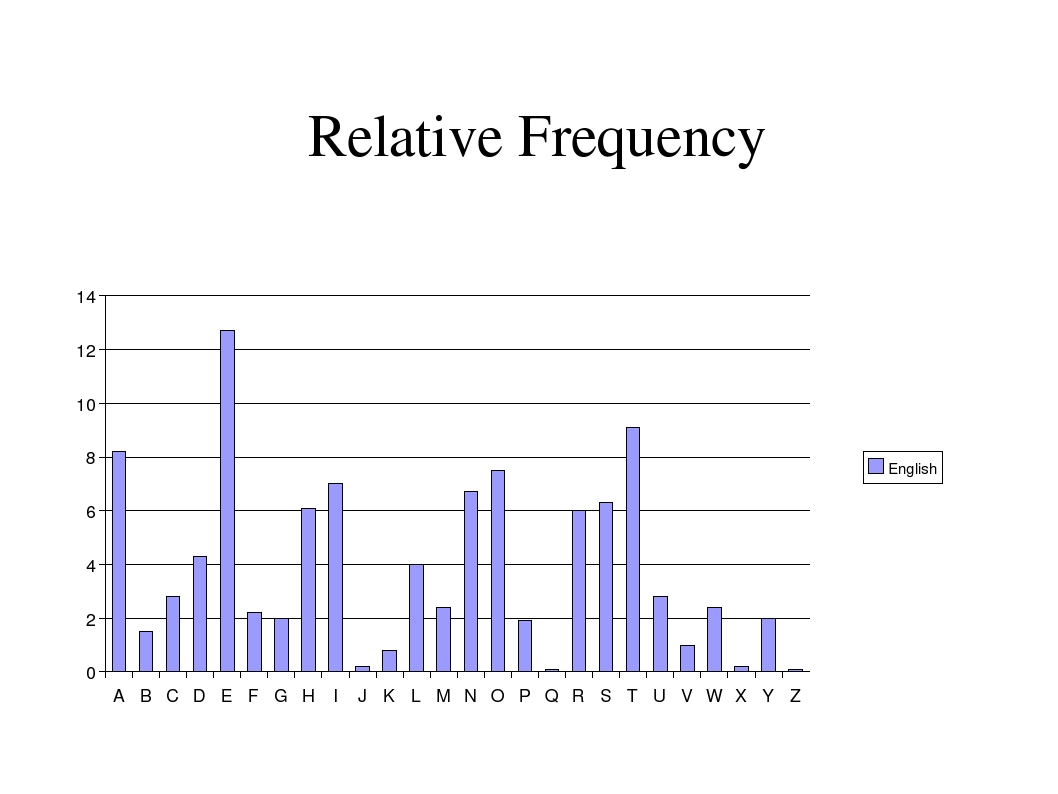

All languages are statistically biased. For example, in English, the letter ‘E’ is used the most, followed by ‘T’ and ‘A’. We can observe the frequencies of all English alphabets in the below graph.

If a block of data is considered, in which every byte is XORed with the same byte, then the resultant block will preserve the same statistical properties as the initial block. For example, we can assume that the number of e’s in the initial block was the highest, from the above graph. If so, then in the resultant block, the byte with the highest frequency can be mapped to ’e’. In similar fashion, we can find the mapping for every other byte.

In repeating-key XOR, if the key length is $k$, then after every $k$ bytes, the same byte is used for XOR. This means that we can put them together to obtain a block of data similar to the one discussed above.

We shall walk through this in a step-by-step manner:

Estimate the key length

We can start with $k=1$ and keep incrementing to find the value for which the normalised Hamming distance is minimum. This will be the possible key length.

Transpose

Put together every $k$th byte to form $k$ groups. Every group is the resultant of XOR with a single key byte.

Frequency Analysis on each group

For each group, brute-force all 256 possible key bytes. For each candidate, XOR the group and score the result for English likeness. We can come up with a scoring system by using the frequency of letters in English alphabets. We can also use the fact that random special characters are rare in an English text.

Assemble

Rearrange the resultant bytes with highest scores, to undo the transpose done earlier. If the answer reads like English, then it is likely the plaintext. If not, repeat the process with different values of key lengths.

Bit Flip Cipher

The cipher I built months back, the Bit Flip Cipher uses SHA256 (32 bytes) as a deterministic keystream and repeats it across the message. That construction is, for the purposes of this attack, indistinguishable from a fixed 32-byte repeating key.

SHA-256 gives good pseudorandomness, but in this implementation it does not remove repetition. So, the Bit Flip Cipher can be broken in the same way.

The digest being pseudorandom makes it harder to find the original key used, but the ciphertext is still unsecure. If the message is long enough, frequency analysis reveals the keystream bytes and the ciphertext bytes.

Defence

- Never repeat a keystream across message bytes.

- Use a cipher with unique nonces (ChaCha20-Poly1305, AES-GCM).

- If you must derive keystream bytes from a key, make them unique to the message. The nonce must not repeat.

Repeating-key XOR is a clean lens into why modern cryptography emphasises randomness and non-repetition.

Related Posts

Fibonacci LFSR: How it works and How to Attack it

The Fibonacci Linear Feedback Shift Register is a classic example of a simple pseudo-random generator. It is often introduced in the study of stream ciphers and cryptanalysis because, while it can produce long pseudo-random sequences, its linearity also makes it vulnerable to attacks.

Read moreBit Flip Cipher: My First Attempt at Making a Cipher

A few months back, I found myself with an idea: what if I tried making my own cipher, just for fun? I hadn’t studied cryptography at all at that point, but I wanted to see how far I could go. That’s how Bit Flip Cipher came into existence.

Read moreUnderstanding Modular Binomials in Cryptography

In this article, I go over a toy model of modular binomials and try to demonstrate how algebraic structure or patterns in a cryptographic system can inherently break secrecy.

Read more